So far in our History of Cheese series, we’ve discussed the ancient origins of cheese, the evolution of cheese in Europe, and the history of cheese packaging. Today, we’re looking at the way that dairy farming and dairy foods like cheese and butter took hold in and shaped the New World as Europeans colonized and extracted resources from the Americas.

Some of us who make a point to support small-scale, traditional dairy farms and cheesemakers working in the U.S. today have an image of these farms as harking back to an idyllic agrarian past in our country. Those farming practices may be more sustainable and produce more flavorful, better quality cheese than methods used by industrial agriculture today. But it’s important to understand how the earliest dairy farms in the Americas impacted Indigenous and enslaved people. The culture of dairy farming that took hold with European colonization wasn’t just a beneficiary of genocide and slavery—it was an active participant.

Central and South America

Before Europeans arrived in the Western Hemisphere, there were no domesticated livestock—so there was no dairy. Indigenous peoples fed themselves through a combination of hunting, fishing, foraging, and agriculture. Even before the Puritans arrived in the New World, the Spanish had begun to colonize Central and South America in much the same way as the English did in the north.

Spanish and Portuguese colonizers brought dairy animals and other livestock, which were allowed to roam freely and proliferate in the lush tropical and subtropical climates. While the fresh Latin American cheeses we know today were developed in response to dairying in tropical climates, there are many cheeses produced throughout Central and South America that are modeled on longer-aged European cheeses: Italian-inspired Reggianito is produced in Uruguay and Argentina, while Swiss influence has resulted in a Gruyere-style cheese being produced today.

North America

In what’s now the United States, dairying took hold with the Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1629, with Puritans from strong cheesemaking regions of England bringing domesticated livestock and cheese recipes with them. The Cheshire and Cheddar-style cheeses they brought would influence cheesemaking in the U.S. for centuries to come.

Between 1630 and 1640, 20,000 Puritans arrived in New England, with nearly every ship carrying dairy cows. The region at the time was heavily forested, so rather than clear lands for pasture, colonists allowed their livestock to graze in the forests, which damaged woodlands that Indigenous peoples in the area used for hunting and foraging.

As white Europeans exhausted soils growing row crops, they began to rely even more heavily on livestock, which could graze marginal lands, for food. A steady stream of colonists coming from England served as a strong customer base for the cheeses they made, as well as other surplus agricultural products from subsistence farming.

After 1640, however, that steady stream of Puritans who needed to purchase provisions from established farmers stopped as conditions for the sect in England improved. Dairy farmers now had to export their products rather than selling them in the colonies. By the 1750s, population began to outstrip land availability. New arrivals headed west and south, bringing dairy animals, butter, and cheese with them and displacing more Indigenous people to claim land for agriculture.

Cheddar was paramount in the early North American export market.

Early American Cheese's Connection to the Atlantic Slave Trade

Starting in the mid-1600s, New England began exporting vast quantities of cheese and butter to provision large plantations in the West Indies, where sugarcane plantations had expanded rapidly and depended on huge numbers of enslaved people kidnapped from Africa. Along with the rum industry in New England—made possible by purchasing large quantities of molasses, a byproduct of sugar refining—dairy farmers there thrived thanks to this business from the Atlantic slave trade.

Enslaved Africans didn’t just consume cheeses from the colonies. In Rhode Island, which dominated the American slave trade starting in the early 18th century, the Naragansett Plantations were huge farms owned by wealthy white families and worked by enslaved people.

The same gendered roles on English farms were reflected on these plantations, with enslaved women working as dairy maids and cheesemakers. The Cheshire-inspired Narragansett cheese produced by these women on these plantations in the 18th century became widely known for its quality and was considered the best cheese produced in New England.

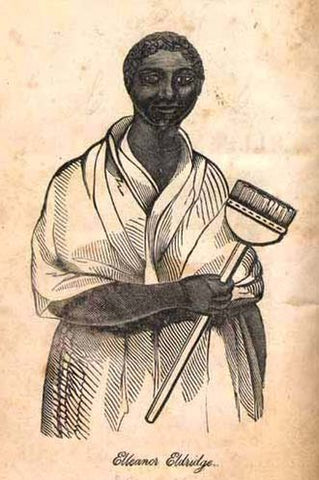

Portrait of Elleanor Eldridge from the frontispiece of the "Memoirs of Elleanor Eldridge"

Elleanor Eldridge, Acclaimed Cheesemaker

While the contributions of Africans and African-Americans to early cheesemaking in the United States have mostly been ignored, at least one of these women is known to us today. Rhode Island-born Elleanor Eldridge was the daughter of a Narragansett Indian woman and a formerly enslaved man who bought his freedom by fighting in the Revolutionary War. After her mother died when Elleanor was a child, she went to work as a servant, where she learned to make cheese, and later worked in a dairy to support herself.

Elleanor is mostly known in history for a landmark legal case in which she successfully sued to reclaimed the house she owned, which had been improperly seized by a lender, and a subsequent memoir written about her. But she stands out in the historical record as a free Black woman in the 19th century who was known for the high-quality cheeses she produced.

Stay tuned for the next installment in our History of Cheese Series, Part 5: The Industrial Revolution and Big Ag!

Sources:

Cheese and Culture: A History of Cheese and Its Place in Western Civilization, Paul S. Kindstedt

The Oxford Companion to Cheese, ed. Katherine Donnelly

Cheese in Latin American Cuisine, Oldways Cheese Coalition

Leave a comment